Article copied from "Films on Screen and Video" December 1982 Vol 3, No. 1

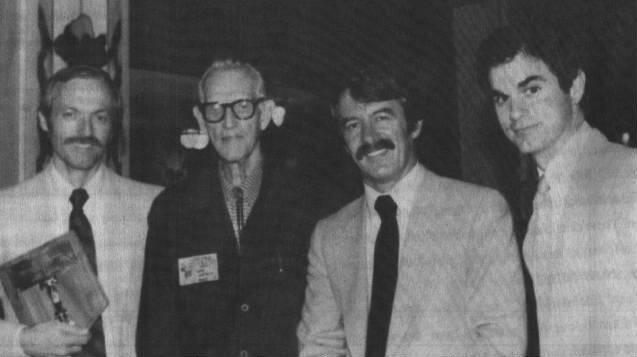

This picture is from "The Animated Films of Don Bluth". The Bluth Group receiving their animation 'Inkpen' award. Pictured left to right Don Bluth, animator Grim Natwick (not related to the Bluth Group), Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy.

THE SECRET OF BLUTH

Article by Iain McAsh

'CLASSICAL' is a word that crops up time and again in conversation with American animation producer-director Don Bluth. He refers to classical stories on the big screen in the cartoon medium pioneered by Disney over forty years ago.

Bluth, with his enthusiastic young partner John Pomeroy, stopped over briefly in London to promote the premiere of his first independent feature, "The Secret of NIMH". As a lifelong animation buff who began my film industry career as a trainee 'in-between' on Britain's first-ever cartoon feature "Animal Farm" for the Hales and Batchelor unit, the time spent with Bluth and Pomeroy in their London hotel was a fascinating experience for me.

Both men did sterling work for Disney studio at Burbank before deciding to strike out on their own after expressing disatisfaction with the techniques now used by their former employers. Under the banner of Don Bluth Productions a brave new animation company was born enhanced by the talents of nineteen former Disney artists who shared their views.

'We wanted to replace the classical, sophisticated style of Disney at his peak.' Bluth explained. 'So a group of us defected from Disney in 1979 when we were mid-way through animating "The Fox and the Hound". Why did we leave? John and I are both great Disney fans. That's why we left the studio - you've answered your own question! The old classical style of animation is gone. Now they're cutting corners by using limited animation. Disney at his peak employed 1,500 artists, including the staff working on all those shorts. We loved the age of classical animation and the five Disney classics: "Snow White", "Pinocchio", "Dumbo", "Bambi" and "Fantasia".

'The Multiplane camera, pioneered by Disney, is part of the classical animation. The problem is it's so large and expensive that it takes four men to operate. We used the Multiplane for "The Secret of NIMH". It's great for achieving depth of background and a three-dimensional quality because all the painted 'cels' are placed at three different levels to achieve this effect. Disney was a master at it. Remember how the camera tracked through the forest in the opening sequence in "Bambi"? It looked almost more realistic than a real forest. For "NIMH" we adapted Multiplane into two cameras which made it easier to use.'

Bluth, like Disney, chose a mouse to rocket him to fame. His heroine is Mrs. Brisby, no less, a widowed fieldmouse with four unruly children. She was created by the late Robert C. O'Brien for his Newbery Award-winning nove, "Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH", recipient of an American Library Prize for Excellence on a children's list. The film was supported by a multi-million dollar merchandise and promotional campaign to ensure that the public will not be unacquainted with Bluth's gallery of pen-and-ink charaters.

Elizabeth Hartman supplies the vocal chords for Mrs. Brisby; Don DeLuise as the comedic Jeremy the Crow; Derek Jacobi as Nicodemus, leader of the rats; Paul Shenar as his lieutenants; Hermoine Baddeley as Shrew; and British-born veteran Arthur Malet (who played Mr. Dawes, the son of the elderly City Banker in Disney's Mary Poppins) as the crotchety old rat, Mr. Ages.

'My favourite charater?' asks Bluth. 'It has to be Mrs. Brisby. She reminds me a lot of my grandmother, whom I loved very much. She had thirteen children; when her husband died she raised the kids, cooked, took in boarders and cooked some more. Mrs. Brisby has parallels. She's very real; there's the plough coming to destroy her house; she has strength and can identify [be identified with?]. The story is about courage, determination and all these qualities are shown in our field-mouse heroine.

'Casting the voices was very important. For each character, we drew up a list of at least twenty actors. We even had Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles on our list at one time. Then John Pomeroy was watching the Merv Griffin Show on T.V., when John Carradine was guesting. He 'phoned me and said Carradine had just the right presence for the Great Owl in our film, who is a terrifying figure and Mrs. Brisby has to have a great deal of courage to face up to him, as everyone knows that owls eat mice. Mr Carradine is 76, and his voice was just what we needed. When he saw a rough cut, he pulled a face and said, 'I like the Owl best!'

Bluth's production of "The Secret of NIMH" employed 122 artists and eleven key animators, including Don and John Pomeroy. John's wife, Lorna, was responsible for the romantic overtures of the crow, Jeremy, who is forever looking for Miss right. The film's score was composed by Oscar-winner Jerry Goldsmith, his first for an animated feature. There are two songs, but there is a great deal of music and each character has its own individual theme.

'The story is the most important thing,' believes Bluth. 'Without it you can't expect an audience to sit through a 90-minute animated film. You must give them something to take up their attention all that time.

'Classical animation has to be highly disciplined. Most of our artists are young. The average age is twenty-two; that's by design, because they're easy to mould. You can't always tell by looking at their portfolios. Some are not very good artists; some cannot draw that well, but some are great actors and make our top animators. That's what makes a good animator. He must be a good actor with a pencil, for he has to act out all the characters he is drawing. And he must also be able to sustain that interest all through a long schedule. "The Secret of NIMH" took thirty months to complete from January, 1980, right through until the final dub in June '82.'

Most newcomers want to be animators, as they are the undisputed 'kings' of the cartoon film industry. 'But some will always stay as in-betweeners,' states Bluth, 'because that's what they're best at doing. Others are effects animators specialising in shadows, reflections in water, snowflakes, raindrops, smoke, that kind of thing.'

Bluth admits he and his artists have disagreements at times, but they get there in the end. As evidence of this he quotes the story of two veteran animators working on "The Jungle Book", which was the last completed animated film at the studio to be personally supervised by Walt. 'One artist didn't like the other one's elephants.' he recalls. 'After a preview screening, Walt said very quietly: 'I think the elephants are the best part of the picture.' That settled the argument. The artist went very quiet, and was put firmly in his place. That was Walt's great talent. He was like the captain of the ship. That's what's missing at the Disney studio now. Walt isn't there anymore.

'Then there was the spinning plates story. A veteran Disney man always asked newcomers to animate a cigar box spinning on a stick instead of plates. A cigar box was difficult to draw instead of the round plates. It had square corners which made it difficult to animate. The young animator finally mastered the square edges and drew the cigar box instead of the spinning plates. It was very clever, but the audience never noticed it. They said so what? It contributed nothing to the finished picture. They thought the spinning plates were funnier! The moral there is don't try to be too clever in what you animate. And you wouldn't believe how many artists claim to have animated the Mushroom Dance in "Fantasia".'

Don Bluth and John Pomeroy entered the animation industry from totally different backgrounds. Texas-born Bluth was for a time a Mormon preacher in Argentina before lending his talents to the Disney studio which he joined in 1955 working on "The Sleeping Beauty". He rose swiftly to charater animator on "Robin Hood"; directing animator on "The Rescuers"; animation director on "Pete's Dragon"; producer-director of the Christmas featurette "The Small One"; and "The Fox and the Hound" which he was animating at the time of his departure three years ago.

Pomeroy, 29, began his Disney career as a trainee later earning his spurs animating the shorts "Winnie the Pooh and Tigger, Too", "The Small One" and the features "The Rescuers", "Pete's Dragon" and latterly, "The Fox and the Hound".

'Unlike John, I wasn't trained at art school,' admits Bluth. 'There were seven children in our family and my father was worried in case I wouldn't be able to support myself. With my brother I spent some time managing a theatre in Culver City where we staged twelve musical comedies. I joined Disney when I was eighteen as an assistant doing layout and animation. John is a very clever modeller. He's great at making puppets, marionettes, making models and sculpting in clay. He qualified from college as an architect, while I only passed in English!'

The two men teamed up on an independent short feature, "Banjo the Woodpile Cat", working evenings and weekends in Don's garage. Another parallel with Disney as all animation efficionados know that Mickey Mouse was born fifty-four years ago in Walt's Kansas City garage. Under the Don Bluth production banner their first collective enterprise was the charming two-minute animated sequence for Universal's live - action "Xanadu", which they completed in a brisk eleven weeks.

Bluth and Pomeroy first became aware of "The Secret of NIMH" - (the initials stand for National Institute of Mental Health) - during thier latter Disney days. 'Lots of books were passed around there, and O'Brien's novel was one of them', Bluth recalls. 'Ken Anderson, one of Walt's veteran storymen, saw the possibilities in it as a feature-length cartoon. We finally got it, and John and I were willing to fund it (through Aurora Productions). It was an uphill job, but the book was very popular and became required reading in American schools. However it did not translate well to film and we had to make some story adjustments.'

Thirty months later "NIMH" was completed at a final cost of seven million dollars. Their next project "East of the Sun, West of the Moon" has been estimated at eleven million dollars, so says Bluth, 'We will be able to splash out a bit more!'

Based in their modern two-storey building in Studio City, California, Bluth and his partners are eagerly awaiting the results of "NIMH" as they look forward optimistically to 'A New Golden Age', a renaissance of classical animation, Bluth believes that the cartoon medium is virtually unlimited with possibilities that no other art or method of film-making can hope to achieve.

He cheerfully concedes that "The Secret of NIMH" (on the surface perhaps an unlikely subject for animation like "Animal Farm", "Watership Down", "Heavy Metal" and the forthcoming "Plague Dogs") is his personal 'baby'. And in that, too, undoubtedly lies the secret of Don Bluth's future success...

This site was created Wednesday 24 December 1997